Our major wine appellations (AOP)

Châteauneuf-du-Pape

The Châteauneuf-du-Pape appellation is the jewel in the crown of the southern Rhône Valley's wine heritage. It was in the 14th century that Pope Jean XXII had a fortress built at Châteauneuf and developed the famous vineyard...

Renowned as much for its white wines as for its reds, the vineyard covers just over 3,000 hectares of vines and produces almost 100,000 hectolitres of wine each year (over 90% reds). It covers almost the entire commune of Châteauneuf-du-Pape and four neighbouring communes (Bédarrides, Courthézon, Orange and Sorgues).

This exceptional terroir, located on the left bank of the Rhône between Avignon and Orange, is made up of vast terraces covered in red clay mixed with numerous rolled quartz pebbles. In the heart of the southern sector, the Mediterranean microclimate is the warmest in the Côtes-du-Rhône.

In addition to these unique growing conditions, the wines of Châteauneuf-du-Pape have also built up their great aromatic richness through the use of a large number of grape varieties, 13 in all, with Grenache Noir remaining dominant. The art of blending...

The vines are pruned into goblets to protect the bunches from the Mistral and the scorching sun. The extreme ripening of the grapes is further enhanced by the famous rounded pebbles, which release all the heat they store during the day at night.

The red wines are fantastically complex. Powerful, full-bodied and well-balanced, they are full-bodied on the palate and have a powerful nose with hints of undergrowth. Their intense garnet-red colour reveals a wide range of aromas: ripe fruit (blackcurrant, blackberry), spices and roasting. They are best enjoyed after a few years' cellaring, with the best vintages reaching maturity after several decades.

Gigondas

Gigondas, Montmirail and its Dentelles, its Saracen tower, the Turkish rock, the Ouvèze... Gigondas and its hamlets are hilly and sunny. This is Provence, with its scents of garrigue and cypress, its colours and jagged relief. A paradise for Grenache. The aromas are peppery, chocolate and red fruit.... No two Gigondas wines are alike, and time is their ally!

The Gigondas AOP covers 1,230 hectares of vineyards in the commune of Gigondas, at the foot of the famous Dentelles de Montmirail. Average production is 35,000 hectolitres of red wine (rosé production is very limited). Gigondas wines are produced on the Ouvèze pebble terraces, and have a reputation for great aromatic finesse.

Grenache is the main grape variety, complemented by the classic varieties of the southern Rhône Valley, in particular Syrah and Mourvèdre.

Gigondas wines are rich and generous, with a tannic structure that is present but ripe. The palate is full-bodied, often fleshy, with good body. The tannins are robust but mellow with age, giving structured, well-balanced wines.

The ripe fruit aromas seen on the nose are repeated, accompanied by spices, pepper, Provençal herbs and sometimes mineral notes. The wines often have a fresh finish, thanks to the relative altitude and limestone soils of the terroir. They can be kept for 5 to 15 years, or even longer for the best vintages.

The Ouvèze

The Ouvèze is a river that flows through the Drôme and Vaucluse departments. It is a left-hand tributary of the Rhône. It flows through Saint-André-des-Ramières.

Nearly 100 kilometres long and passing at the foot of Saint-André-des-Ramières, it rises in the Chamouse mountain, near Somecure, in the Baronnies massif north of the Vaucluse plateaux. It flows westwards through Montguers, Buis-les-Baronnies, Pierrelongue and Mollans-sur-Ouvèze. In the Vaucluse, it continues north-west of Mont Ventoux and north of the Dentelles de Montmirail to cross Vaison-la-Romaine.

After Vaison, it flows through a fairly wet plain between Rasteau and Sorgues. The Ouvèze joins the Rhône on its left bank, passing to the west of Sorgues opposite the Barthelasse island.

Its main tributaries are the Toulourenc, the Seille, the Sorgues, the Canal de Vaucluse and its branch, the Canal du Griffon, the Menon, the Eyguemarse, etc.

Vacqueyras

Vacqueyras AOP is produced in the communes of Vacqueyras and Sarrians, north-east of Orange. The terroir covers around 1,400 hectares of vines, bordered by the Gigondas and Beaumes-de-Venise vineyards.

Annual production is just over 32,000 hectolitres. The vineyards are planted mainly at the foot and on the slopes of the famous Dentelles de Montmirail massif and on the Ouvèze river terraces. The soil is extremely diverse, consisting mainly of clay, sand, pebbles, limestone scree and red limestone. The grape varieties planted here are traditional for southern Côtes-du-Rhône vineyards, and this combination of climate and soil produces red wines of varying character (as well as a few rosés and rare whites).

The reds are mainly made from Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre and Cinsault.

Full-bodied, round and rich on the palate, Vacqueyras red wines have notes of red fruit and violets, as well as liquorice and undergrowth. These are wines of character, well-balanced and fine, best enjoyed after two or three years.

Rasteau

The Rasteau AOP is produced in the communes of Cairanne, Rasteau and Sablet, in the Vaucluse.

Recognition as a AOP dates back to 1944 for vins doux naturels and 2010 for dry red wines. Covering an area of 733 hectares, this terroir produces around 25,000 hectolitres annually.

The ancient alpine diluvium terrace is composed of a matrix of red clay, rich in rolled quartz pebbles and grey limestone.

On aeration, the red wines give off a nose of blackcurrants and sweet spices. Fleshy and well-structured, they have good ageing potential.

Ventoux

The Ventoux AOP covers 6,700 hectares at the foot of the famous Mont Ventoux. The terroir is divided into 3 wine-growing sectors: the Malaucène basin in the north, the Carpentras amphitheatre in the centre, and the southern sector, which borders the Luberon vineyards.

The Ventoux AOP produces around 285,000 hectolitres of wine each year, mainly reds (85% of the volume), but also rosés and rare whites.

The soils are generally derived from Tertiary sediments, hard limestone, scree and ancient stony alluvium. Although divided into 3 sectors, the Ventoux vineyards benefit from fairly homogenous climatic conditions that are highly conducive to producing quality wines. It benefits from the sunshine and heat typical of the Mediterranean climate, while being well sheltered from the winds by the surrounding mountains.

The wines are made from a variety of grape varieties, mainly Grenache Noir and Syrah for the reds. They are often fruity, and can be supple and light, or more marked by powerful tannins and more colour.

Côtes-du-Rhône

The Appellation area stretches from Vienne in the north to Avignon in the south. The vineyards are divided into two regions : Côtes-du-Rhône septentrionales (from Vienne to Livron-sur-Drôme) and Côtes-du-Rhône méridionales (from Montélimar and Bourg-Saint-Andéol to Avignon). The production area covers 29,000 hectares. Annual production averages 1 million hectoliters. The Côtes-du-Rhône appellation covers 172 communes in six départements (Rhône, Loire, Ardèche, Drôme, Vaucluse and Gard).

The vineyards are divided into two main areas: the Northern Rhône (to the north) and the Southern Rhône (to the south).

In the southern part, the climate is Mediterranean, with hot, dry summers influenced by the mistral, a powerful dry wind that helps to keep the vines healthy by limiting humidity. There is a wide variety of soils.

Syrah is the main grape variety in the northern Rhône, while Grenache dominates in the southern Rhône. Other grape varieties include mourvèdre, carignan and cinsault.

But let's go back in time. In the 13th century, the viguerie of Uzès was divided in two. There was the viguerie haute or Cévennes, and the viguerie basse which took the name of the Côte du Rhône. The wines of the Côte du Rhône were renowned. Regulations were introduced in 1650 to protect their authentic origin and guarantee their quality.

An initial royal edict dated 27 September 1729 attempted to give this small region a wine-growing identity. However, it proved insufficient and was amended in 1737 to read as follows: ‘All barrels of wine destined for the sale and transport of wine from Roquemaure as well as from neighbouring and contiguous places and parishes: Tavel, Lirac, Saint-Laurent-des-Arbres, Saint-Geniès-de-Comolas, Orsan, Chusclan, Codolet and others which are of superior quality will be marked on one of the bottoms, being full and not otherwise, with a fire mark which will contain the three letters CDR meaning Côte du Rhône with the vintage year. ’

This name flourished, as in 1783, a member of the Académie de Marseille stated that ‘The Côte du Rhône is as renowned for the finesse of its oils as for the bouquet of its wines’

In 1869, a local newspaper ran the headline ‘La Côte du Rhône’, and in 1890, Frédéric Mistral spoke of ‘Costo dou Rose, renowned for its wines’. It wasn't until the 20th century that the Côte du Rhône became the Côtes du Rhône, extending to the vineyards on the left bank of the Rhône. The creation of the Syndicat général des vignerons des Côtes du Rhône in 1929 by Pierre Le Roy de Boiseaumarié was a decisive step in this expansion. This reputation, acquired over the centuries, was validated by the Tournon and Uzès Regional Courts in 1936. The Appellation was created by decree on 19 November 1937.

Mont Ventoux

Mont Ventoux is the summit of the Vaucluse and the giant of Provence. Reaching an altitude of 1,909 metres, it is approximately 25 kilometres long on an east-west axis and 15 kilometres wide on a north-south axis. Nicknamed Mont Chauve (Bald Mountain), its geographical isolation makes it visible from great distances. It forms the linguistic boundary between North and South Occitan. It is the giant of Provence.

Before it was criss-crossed by three main roads, which have enabled the development of green tourism and outdoor sports in both summer and winter, notably with the organisation of major cycle races, motor racing and other events, the mountain was criss-crossed by tracks laid out by shepherds following the boom in sheep farming between the 14th and mid-19th centuries.

Lucien Lazaridès was the first rider in the Tour de France

to cross the summit of Mont Ventoux. It was in 1951.

From 1902, it was on the 21 km route de l'Observatoire,

one end of which is 293 metres above sea level and the other 1912 metres,

that the first Mont Ventoux hill climb took place.

It was won by Paul Chauchard in a Panhard et Levassor.

The mountain's remarkable whiteness is due to its predominantly limestone composition and the numerous scree slopes at the summit. The mountain also features intense karstification due to water erosion. Rainfall is particularly abundant in spring and autumn. Rainwater infiltrates the galleries and gushes out in resurgent springs of varying flow, such as the Fontaine de Vaucluse and the Grozeau spring.

Mont Ventoux is subject to a predominantly Mediterranean climate, which is sometimes responsible for scorching summer temperatures, but the altitude also means that there is a wide variety of climates, from the summit to a mountain-type climate, including a temperate climate at mid-slope. What's more, the wind can be very violent, with the mistral blowing almost half the year. This particular geomorphology and climate make it a rich and fragile environmental site, with many different levels of vegetation, as demonstrated by its classification as a biosphere reserve by UNESCO and as a Natura 2000 site.

Although there is evidence of human settlement in the foothills during prehistoric times, the first documented ascent to the summit was made on 26 April 1336 by the poet Petrarch from Malaucène on the northern slopes. He later paved the way for numerous scientific studies. Subsequently, for almost six centuries, Mont Ventoux was intensively deforested, for the benefit of the shipbuilding industry in Toulon, charcoal manufacturers and sheep farmers.

While sheep farming has all but disappeared, bee-keeping, market gardening, wine-growing, mushroom picking (including truffles) and lavender cultivation are still practised.

Because of all these features, Mont Ventoux is an important symbolic figure in Provence, having been the subject of oral and literary accounts, as well as numerous artistic and scientific graphic representations.

In Occitan Provençal, Mont Ventoux is known as Mont Ventor according to the classical standard or Mount Ventour according to the Mistralian standard.

The original name Ventour already appears in the 2nd century in its Latin form Vĭntur on three votive inscriptions to a Celtic god. The first was discovered in the 18th century at Mirabel-aux-Baronnies, on the site of Notre-Dame de Beaulieu by Esprit Calvet. It reads VENTVRI / CADIENSES / VSLMN. The second, from Apt, was found in 1700 by Joseph-François de Rémerville, who wrote VENTVRI / VSLM / M. VIBIVSN. The third was unearthed during excavations in 1993 at the chapel of Saint-Véran, near Goult, where only VINTVRIN remained legible on a fragmenta.

While this oronym passed into Provençal without much change, the same cannot be said of its clever Latin reworking, Mons Ventosus, which has been documented since the 10th century and was the term used by Petrarch in the 14th century. Following in the poet's footsteps, it was for a long time reinterpreted as ‘windy mountain’, given that the Mistral wind often blows here at over 100 km/h, and sometimes much more.

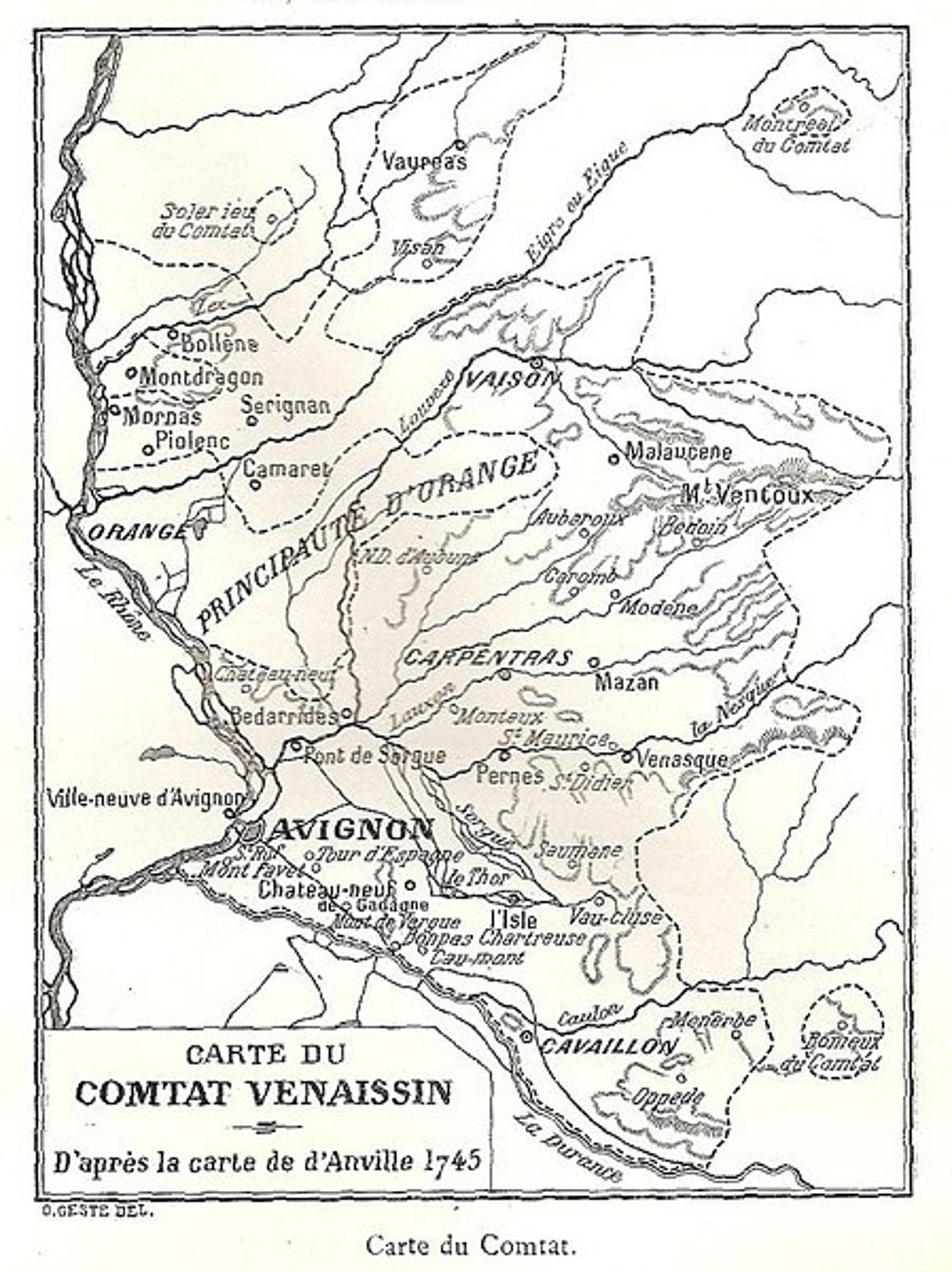

The Comtat Venaissin

The Comtat Venaissin, often referred to as the Comtat, is a former papal state. It was founded in the Middle Ages, in 1125, and was completely dissolved on September 14, 1791. In other words, it lived for almost 700 years !

It stretches between the Rhône, the Durance, Mont Ventoux and the Dentelles

de Montmirail and includes the towns of Carpentras, Vaison-la-Romaine, l'Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, Cavaillon...

80 current communes made up the Comtat Venaissin, spread between the departments of Vaucluse and Drôme. Today, 10% of these communes are in the southern part of the Drôme département, while 90% are in the Vaucluse, which it covers almost entirely.

The Comtat was created as a result of the ‘Grande Provence’ partition treaty, signed on 16 September 1125 between the Count of Toulouse (Alphonse Jourdain) and the Count of Barcelona (Raymond Bérenger). This treaty granted the northern territory, covering the land between the Durance and Isère rivers, to the Count of Toulouse, which became the ‘Marquisate of Provence’. It was within this Marquisate that the famous Comtat Venaissin was to be found, and it also made up the majority of the territory. The southern part of the region was handed over to the Count of Barcelona before becoming known as the ‘County of Provence’.

At the beginning of the 13th century, the Church embarked on a war epic known as the ‘Crusade against the Albigensians’ (1208-1229), aimed at wiping out Catharism, which was widely established in Languedoc, particularly in the lands dominated by the House of Toulouse. Raymond VI, heir to the Comtat, was considerably weakened and forced to go on crusade. King Louis VIII subjected Raymond VI to the Treaty of Paris, signed on 12 April 1229, which divested the House of Toulouse of its lands and divided them between the Church and the King. The Comtat Venaissin was then handed over to the Holy See.

This was followed by a turbulent period during which the dispossessed were able to make claims on the land, supported by important figures of the time.

The Comtat was finally handed over to Pope Gregory X on 27 January 1274. The Papacy thus retained control of the Comtat until 1790, based on a monarchical government legitimised by the will of God.

It was not until 14 September 1791 that the Comtat was attached to the States of Avignon, following a vote by the National Assembly. The Comtat was eventually incorporated into the department of Vaucluse, the creation of which was decided by decree of the National Convention on 25 June 1793 (along with the cité État of Avignon, the principalities of Orange and Mondragon, the county of Sault and the viguerie of Apt).